Most publications have a style guide setting out how they would like you to use speech marks or spell out numbers. This one in particular has another clause, set in by my editor Shini, which expressly mandates a dad joke or a reference to a meme. She doesn’t care much for air-tight grammar, either, although I have a feeling it’s to loosen us up a little. “‘Tis the internet, after all, and our readers are probably reading this in a bus to work, ENTERTAIN, EDUCATE!” I like to think that if she were a football coach, there’d be hip hop blasting from a (Bosé) speaker before each game.

I digress. As fashion writers, before submitting a piece of news or writing, we’re encouraged to read the style guide, digest the style guide and abide by the style guide. No questions. There’s a holy grail version floating out there in some sort of telephatical form (with a small ‘Vogue TM’ stamp nearby, I’m sure) banning words like chic, Parisian chic, reinvented, authentic (the list is endless) from being used—unless ironically.

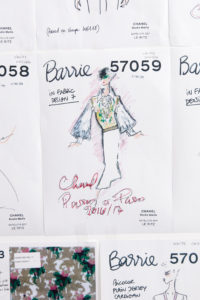

But, voila, the French New Wave comes along and we momentarily forget the rules because Chic makes a brief comeback, and she’s brought Parisian along with her donning sophisticated stripes. Here’s some context.

Originally popularised by the snappy, left-wing weekly l’Express, the term “Nouvelle Vague” (or New Wave) was at first applied to the postwar generation of forward-looking youth bringing new ideas to French political life. After World War II, there was an understandable cultural need to shift away from the old and embrace the new which was also heavily influenced by the establishment of Charles de Gaulle’s Fifth Republic in 1958. Likewise, all sorts of new movements cropped up throughout Europe, including “new theatre” and the “new novel.” This was art world’s own #metamorphosis.

Several key directors and archetypes of the New Wave (François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Claude Chabrol, Jacques Rivette, and Eric Rohmer) initially began their careers as rebellious and dynamic young critics for Cahiers du Cinéma, France’s leading film monthly, before demonstrating that low-budget and creatively financed movies could become commercial hits. (Though creative personnel other than directors should be considered part of the nouvelle vague too, including: screenwriters and cinematographers such as Bernard Evein, as argued by Richard Neupert in his refreshing and authoritative examination of the movement A History of the French New Wave Cinema.)

Jean-Luc Godard’s Une Femme Est Une Femme appeared in 1961, presented with a fine splashy comic use of colour and an exuberant jump-cutting pace. “A consciously playful relationship with the cinema audience is established by winks, gestures, sometimes direct address,” writes Henry Heifetz in his 1964 review which appeared in Film Quarterly. “Music is used arbitrarily for particular comic effects; improvised bits and visual gags come pouring out one after another… But, as in other Godard movies, the camera continually adores two objects: Anna Karina and Paris, which carry the emotional charge of the film.”

Sometime reality is too complex. Stories give it form.

Jean Luc Godard

In the spirit of youth and rebellion, the protagonist is playful and unafraid of being creative and unconventional. Angéla (Anna Karina) wears clothes that punctuate her playful personality, opting for berets, tartan and vibrant reds that encapsulate her character and spiritedness. Theatricality is swapped for effortless Parisian nonchalance in Godard’s first film Breathless (1960) starring Jean Seberg, sporting easy stripes and a classic trench coat that inspires energy and movement. Fresh and modern, she navigates the city streets with an ever-present insouciance and grace – two crucial qualities that complete a quintessentially carefree ensemble. C’est chic.

Comments